Writer’s block and product management

Every time I sit down to write, there’s this speed bump I have to get over before I can get started. One part of it is procrastination and having to summon up some activation energy. But if that was all, I’d not be writing this post. Staring at a blank screen is intimidating. The mind’s blank and full at the same time. Writing forces me to crystallize my thoughts. I have to think deeply in order to write something clear and coherent. It forces me to think deeply about the topic, why I care about it, why my reader should care (I haven't cracked this yet), and what I truly know.

We all like to think that we have good mental models of the world, ones that hold up to the most exacting scrutiny. We don’t owe our opinions anything, and should be ready to throw them out when new data emerges. To do this, it is good to do the hard, unpleasant work of doing regular audits on what we think we know. Writing’s the best tool I have found for the job. Unless we teach, talk or write at length, we are prone to believe we know more about a subject than we actually do. We hold a jumble of thoughts and opinions in our head that we confuse for a clean and coherent mental model. In the rest of this post, I’ll talk about how I thought I knew product management, and how writing forced me to confront my pitfalls and blind spots.

I like to think I know what being a product manager is about. When I was looking to switch out of my first job as a product analyst, I read quite a few books on product management, primarily focused on breaking into the field. Cracking the PM Interview, The Product Manager Interview, The Design of Everyday Things, Don’t Make Me Think and many others. With a few books under my belt and a bunch of YouTube videos on my watchlist completed, I felt I knew almost everything there was to know about product management. It seemed like a simple job.

- Talk to customers

- Decide what to build

- Build???

- Profit

3 years later, I realize was wrong. Quite confidently wrong, in fact. As always, the devil is in the details. It's not that the 4 steps listed above are wrong. It was about being able to do them, consistently. I didn’t actively think about this until one of my friends, during one of our conversations, asked me what product management fundamentally was about. I gave him some answer, but I found it extremely irritating when I noticed that I didn’t have the answer down pat. I wasn’t clear about it. I couldn’t accurately distill down what I thought product management was fundamentally about. That irritation I felt was a pretty strong signal. I knew there was a reason my brain was irritated, just like it is when I try to muster up the willpower to do some weights. My brain knew it had to work hard, so it was protesting.

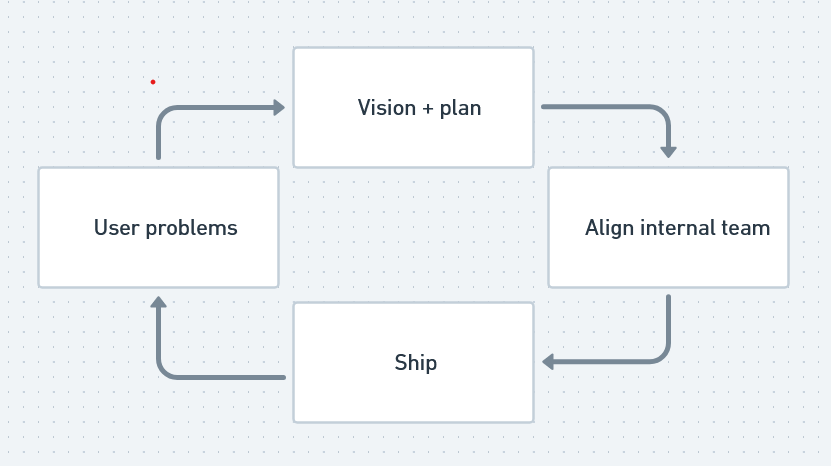

Well, now I’ve forced myself to think about it. As a product manager, you understand your users and their problems, create the vision of a product that solves these problems, sell that vision to the people you work with, build and put it in front of the users. Repeat. The job is about two fundamental things: people and agency. You can’t do this well without understanding people, and you can’t do this at all without being driven.

People: Understanding people and dealing with them is an extremely essential part of being a product manager. You need to understand people well to know what to build and what will get used. For all the breathless adulation Steve Jobs gets, his focus on the end user was noteworthy. Distil everything down to what the user cares about. But understanding your users and their problems is only one part of the people puzzle. You also have to build something for your users, and that’s where dealing with the people in your company comes in. You need this to translate your product vision to reality. PM’s are useless in a vacuum.

I like to think of companies in the context of organisms, even if the analogy is quite tortured. We can think of companies as organisms that transact with the public superorganism via money in exchange for relevant services. In this context, each company has multiple organs that perform their own function (It’s fun to think of sales as the gastric system lol). Product, to extend this analogy, plays the part of the peripheral nervous system, converting intention to action. There are many ways to interact with internal stakeholders: developing and leveraging relationships, using data, understanding game theory, politics and incentives. It is often a combination of these that gets the job done.

Analogy aside, using the lens of human psychology, game theory and behavior is one of the most helpful ways a product manager can frame problems, both internal and external. The level of empathy needed differs sharply based on the breadth of the market you are targeting. Hooked talks about building products that hack the dopamine reward cycle that's common to all humans, and while it’s great for building Snapchat, it is slightly (only slightly) less relevant for building Postman.

Agency: A high agency, low skill product manager ships and learns a lot more over a 5-10 year horizon than a low agency, high skill product manager. The mental makeup of high agency individuals predisposes them to statistically higher rates of success. High agency means you shoot at the hoop a lot more.

Reductive example: There are 2 PM’s, high agency Aurangzeb and low agency Babar. We will assume they’re in a feature factory where more features equals more success. Aurangzeb releases 1 feature every sprint at a success rate of 40%. He’s high agency, so he makes the effort to learn and improve his success rate by 0.5% every sprint. Babar releases 1 feature every 2 sprints at a success rate of 90%. He’s very smart but has low agency, so he often makes the right decision, but it takes very long for him to get stuff done, and his success rate stays flat. After 50 sprints (~ 2 years)

Aurangzeb: 50 features released, ~28 successful feature releases

Babar: 25 features released, ~23 successful feature releases

Working hard and being fast pays off a lot in product management. By virtue of him being a high agency product manager, I’d also bet my house the team places a lot more trust in Aurangzeb than in Babar. Put yourself in the shoes of their teammates. You are a salesperson talking to an important client. You need to bag this client so that you can use the commission to go on that Bali trip you’ve been planning for a while. But you can’t close the deal with this client unless your tech team builds a feature that’s been in the roadmap for a while. There isn’t a lot of time, as is the case with most deal timelines. Who do you go to? Unless it’s a business critical showstopper where getting everything just right is absolutely the top priority, I’d go to Aurangzeb. The speed pays for itself by allowing you more iterations and more opportunities for learning. Even if you were to make a mistake, with Aurangzeb at the helm, you can rest assured it will be fixed faster and you’ll learn more from it.

What makes a great product manager? What differentiates a top 5% product manager from the rest of the bunch? I've had the good fortune of working with quite a few product managers over the years, and have been lucky to witness a couple of great ones up close. Three common traits of all the great product managers I’ve worked with:

- Curious. Love learning. Interested in a lot of things.

- High agency. They get shit done.

- Great listeners and good empathy. They make people feel heard. Being able to do this day in day out, across multiple teams and meetings, is a superpower.

What does this spiel about product management have to do with writing and what did I get out of it? While writing this post, I didn’t learn anything that I didn’t know before. It however forced me to assess the parts of my job, look at them critically, and figure out what the most important parts of it are. I recognize that a high level note like this necessarily glosses over a lot of nuance and differences that are naturally specific to industries and companies. The writing process has crystallised high agency as a central element to high performance in product management, and gives me a solid base to work upon for improving myself. And when my family members ask me what I do for a living, I’ll send them a link.