Tharoor, The Great Divergence and Colonialism

Lucien Febvre cautioned that historians must resist the urge to bring to bear "our ideas, our feelings, the fruit of our scientific inquiries, our political experiences, and our social achievements” on the past. Of course, this is hard with powerful, sensitive topics like colonialism. 8 years ago, Shashi Tharoor gave a speech at the Oxford Union Society on the topic, “Does Britain owe reparations?”. The YouTube video garnered 10 million views, became a major hit, and sparked a divisive response, with Indian sentiment heavily in favor of the views expressed by Tharoor. The speech has since been expanded on in a book that occupies pride of place in every bookshop in India, “An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India”. Tharoor argues for symbolic reparations from the UK, hardly a combustible talking point. The central point of the argument is this:

“At the beginning of the eighteenth century, as the British economic historian Angus Maddison has demonstrated, India’s share of the world economy was 23 percent, as large as all of Europe put together. (It had been 27 percent in 1700 when the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s treasury raked in £100 million in tax revenues alone.) By the time the British departed India, it had dropped to just over 3 percent. The reason was simple: India was governed for the benefit of Britain. Britain’s rise for 200 years was financed by its depredations in India.“

As someone who’s been raised on stories of the Indian independence struggle, I loved this speech. I loved the way it was delivered, and I loved that it stirred up significant conversations that needed to be had about India and its relationship to its colonial past, the silent shadow of which looms over our relationship with the rest of the world. But I wanted to separate sophistry from fact. In this post, I wanted to confirm whether these 2 statements are true, “India was rich. India was looted by the British.”

“At the beginning of the eighteenth century, as the British economic historian Angus Maddison has demonstrated, India’s share of the world economy was 23 percent, as large as all of Europe put together. By the time the British departed India, it had dropped to just over 3 percent.”

Shashi Tharoor speaks well and is able to tap into an ingrained belief that almost all Indians hold, myself included. It is a widespread feeling and teaching that's passed on to every Indian in history class or at home, "India was quite well off before the British looted the country". Given the horrific legacy of the British Raj, this is an understandable story for the nation to tell itself. The data, however, only seems to confirm the latter part of the statement. India was never a particularly rich country. Tharoor quotes Angus Maddison’s claim that Indian GDP was 24% of the world's, but neglects to mention that India also held around 27% of the world's population around then. This means that in 1700, India was slightly below the world's average GDP per capita. Research from Broadberry and Gupta supports this assertion. That's not to mean Maddison’s claims are perfect.

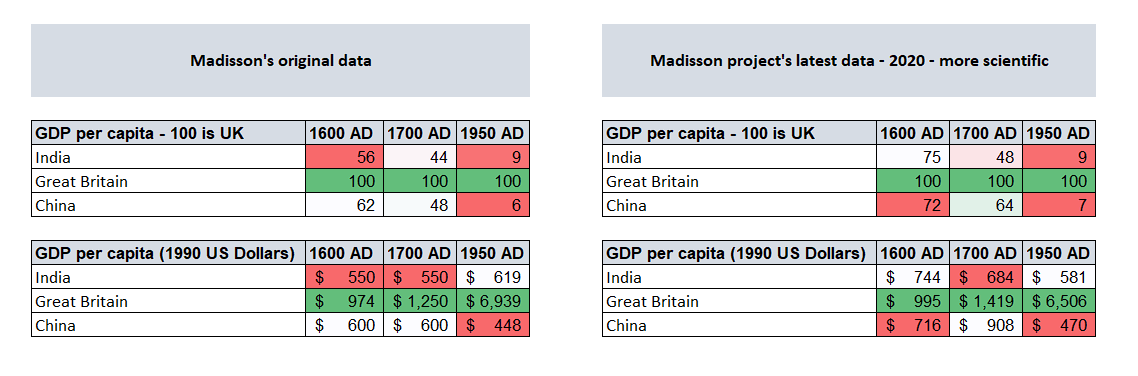

Angus Maddison, in his 2010 report on the history of the global economy, does say that 24% of the world economy’s GDP was Indian. However, his methodology for calculating this data was not reliable and involved too many assumptions. This isn’t an indictment of his work; he was trying to collate the economic history of the world, so there were always going to be some gaps in methodology. Maddison’s numbers have been updated with more scientifically rigorous calculations in the 2020 version of this dataset, and the numbers now say that in 1600, the population in India saw roughly 75% of the money that was seen in the UK. In 1700, these numbers had fallen to about 50%. In 1950, the per capita income of India was 1/11th that of the UK.

So yes, we can quibble about the numbers, but the trend is quite clear - even in the updated datasets, India has been poorer than the UK from the 1600s, though the difference accelerated dramatically over the next 350 years. Numbers also show no indication that the Indian citizen was richer than the world average in 1600 or 1700. Numerous historical accounts during the Mughal period also talk about the astonishing divide in riches and quality of life between the rich and the poor. India was by and large a deeply feudal country, where high taxes went to support a small society of the nobility, while the rest of the population lived in poverty, hardly something we are unfamiliar with. A simple explanation for India being close in GDP around the 1600s, while never being rich is that the entire world was poor, or close to subsistence level life, until technical advancements enabled industrialization. India was in the same boat, more or less. Difficulty in calculating historical economics also leaves us with no way to be more confident.

The numbers also show us a sharp difference in growth rates of living standards between European and Asian economies during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. This phenomenon is called the Great Divergence, though there is quite a bit of disagreement between scholars on the impact that colonialism had on economies, both the colonizers and the colonized.

Why did the Great Divergence happen? We know that in Europe, the decline in prices for cotton yarn, cloth, iron, and other manufactures was unprecedented. The export of these goods led to deindustrialization in India, China, and elsewhere. Free markets, property rights, the existence of nation states, and the famed rational European mindset are all arguments advanced to explain why Europe grew rich. Parthasarathi rejects these beliefs and says that these are inherently Orientalist beliefs. He argues that Europe and Asia faced differing pressures, which led them to prioritize different areas of the economy.

One major factor in this is Indian competitiveness in cloth manufacture. Indian wages were low, which made their cloth extremely competitive on the world stage. This spurred intense competition in the English economy, contributing to the development of techniques that reduced human involvement, the main stumbling block for Europe being lower populations and higher wages.

Another major factor was wood, which was essential for fuel. England in particular faced problems with a lack of wood due to deforestation, which spurred the use of coal, which in turn led to significantly higher energy consumption and technical advancement. India on the other hand always had immense amounts of timber well into the 20th century, lessening the pressure to adopt coal as a fuel.

These two factors taken together paint a slightly different picture. India and Europe were roughly similar in living standards during the 16th century. Both economies were comfortably above subsistence-level wages, with high-income disparity brought about by a feudal economic system. The pressures that were faced by Europe, and England in particular, were absent in the Indian subcontinent, which led to Europe being forced to innovate and find technologies that leapfrogged them ahead of Asia.

With this context, let us talk about the second sentiment in Tharoor’s statement.

“The reason was simple: India was governed for the benefit of Britain. Britain’s rise for 200 years was financed by its depredations in India." It is inarguable that British occupation siphoned away a large amount of money from the Indian economy, which found its way into the British economy. The scale of this siphoning is hotly debated, with some research suggesting that the British economy wasn't greatly helped by India. This could be a fun rabbithole for further research. This also raises another interesting question. What would have happened to India if the Europeans hadn't colonized the country?

Many modern commentators say that the Indian subcontinent, for all its problems with colonialism, wouldn't even exist in its current state if it weren't for the British Raj. Amartya Sen aptly answers this question. If the British hadn't conquered India, it is extremely hard to guess with any confidence what course the history of the Indian subcontinent would have taken had the British conquest not occurred. Would India have moved, like Japan, towards modernization in an increasingly globalizing world, or would it have remained resistant to change, like Afghanistan, or would it have hastened slowly, like Thailand? India was indeed in flux in the 1700's. This period saw both the fall of the Mughals and the rise of British power in India. In the absence of Europeans, it is very possible that India would have been united under another ruler, analogous to most of Indian history, which is marked by alternating periods of tumult and relative consolidation. What impacts this would have on the expanding economy, one can only guess.

If India were to be a major power during this period, its economy would have to industrialize on par with Europe, which would only be possible if there was a large and growing trade + manufacturing section of the GDP. As discussed previously, these economic pressures to find higher quality fuel sources, and to compete with rising international trade competition weren’t strongly felt in India. By the time Indian manufacturing was under threat, it was already controlled significantly by the British East India Company and the Raj thereafter. In the absence of the Raj, the expanding need for resources would have pressured the Indian economy to adapt to technological advances and join the race for industrialization.

Some more notes on real purchasing power - India v/s England

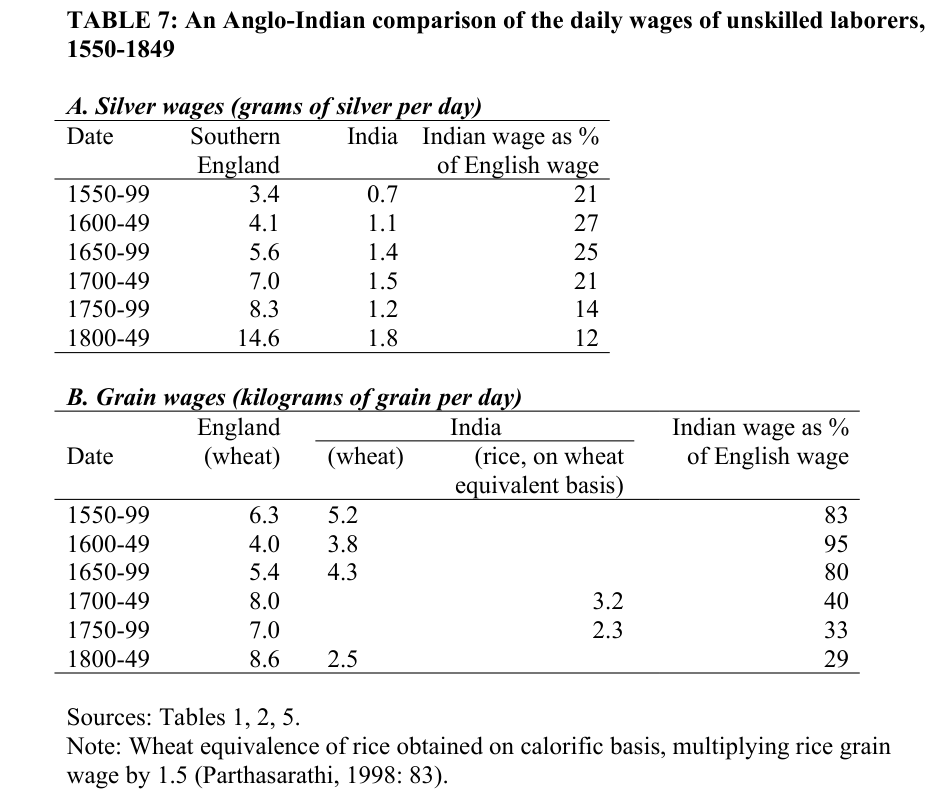

To generally understand the progression of life quality in India and England, I looked at the metrics of how rich the average Indian or English laborer was. A good heuristic for measuring the income of an average individual in the 1600s-1900s is to look at the amount of grain and silver you could buy with the wages of an unskilled laborer.

We can see English grain wages rose heavily in the early 1700s, around the time when Indian grain wages began to fall severely. One explanation for falling Indian wages could be the fall of the Mughal empire which plunged India into multiple civil wars and turmoil. Civil war is terrible for food capacity in an agrarian economy.

What’s interesting here is the silver wage pattern. Indian labor never really had the ability to purchase silver on the same scale as the English, even in the 1500s. Silver wages are taken as a proxy for industrialization, the assumption being that more silver and related goods are available in a more industrialized economy. What does this mean for India and England? Indians could eat food in their own country but were limited to their agricultural output, which was significantly lower than England’s. Manufacturing cloth in India was relatively expensive for Indians (constantly getting cheaper), but precisely since Indians didn’t earn much, their low labor prices meant they could export cloth at competitive prices to that of more advanced economies like England. This was however used by the EIC and then the British Raj to use India as a dumping ground for cheap cloth produced by England, a conscious decision to kneecap Indian industry and render the Indian economy unable to compete. This ties in well with Parthasarathi's argument that India hadn't faced evolutionary economic pressures by the time the Europeans arrived, and after their arrival things quickly changed, leaving India unable to modernize.

To summarize, even before the British arrived, India wasn’t technically advanced, with a heavily agrarian economy and significant poverty. The focus on agriculture led to most of the people being able to live off grain but this also meant that India was able to export cloth at competitive prices. It should also be noted that India was a grain-rich country with rice and wheat bowls in the Punjab, Bengal and South India. With a population that was easily fed and an advantage in cloth manufacturing, the Indian economy didn’t face pressure to innovate technologically.

If colonization had not occurred, India's progress in competitive manufactured goods could have continued under a unified, peaceful regime. Looking at the broad strokes of Indian history, there is no reason to suspect that a political consolidation of the Indian subcontinent was impossible without British intervention. So, to recap:

- India wasn’t very rich. India was around/slightly below the global average GDP per capita before the British landed.

- India and England faced significantly different economic pressures. The ones that England (and Europe) faced forced them to look for technological innovation. This wasn’t the case for the Indian economy.

- The collapse of the Mughal empire wreaked havoc on the progress of the Indian economy. Even if one were to assume that the Europeans didn’t arrive, India still needed a unified economy and peace to progress on the path to development.

- Tharoor was right that India was left penniless by the British.

But if the Europeans hadn’t come, it is a matter of personal opinion whether India would have been united under an indigenous ruler. The implications of a victor arising from the melee of multiple warring countries, bearing the beacon of native technical prowess and economic mastery would make for fantastic alternative history fiction.

Sources

- The Early Modern Great Divergence: Wages, prices and Economic Development in Europe and Asia 1500-1800

Stephen Broadberry and Bishnupriya Gupta - India and the Great Divergence: an Anglo-Indian comparison of GDP per

capita,

1600–1871

Stephen Broadberry and Bishnupriya Gupta - Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030AD: Essays in macroeconomic history, Angus Maddison

- India’s De-industrialization under British Rule: New ideas, new evidence

David Clingingsmith

Jeffrey G. Williamson - Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850

Prasannan Parthasarathi